With all the hoopla that surfaced in the mid 2000s about PCBs in farmed salmon plus the concerns about its environmental impact, health guru Dr. Andrew Weil and many others have been touting wild Alaskan salmon as your premium choice. But is the answer really that simple? Bear with me; it’s taken 6 months of this anti-cancer investigating to find out.

To answer that question, we’ve first got to ask a few more: How clean are the waters your fish has been living in? What’s in the food it’s been eating? And because the contaminants we’re concerned about live in fat and accumulate over time, we’ve got to ask: How old and fat is that species we’re eyeing?

QUESTION 1: HOW CLEAN ARE THE WATERS YOUR FISH HAS BEEN LIVING IN?

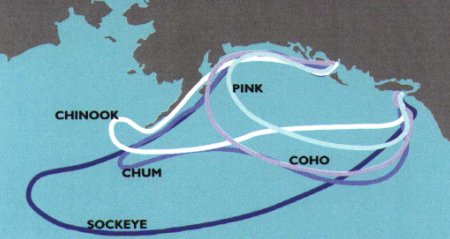

Each species of salmon largely follows the same migration pattern, says Dr. David Welch, whose research provided the basis for this map.

Dr. David Welch has spent his life studying salmon migration patterns. He’s formerly a staff scientist with Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) and now president of Alaska’s Kintama Research, a consulting group studying the marine migration and survival of wild Pacific salmon.

From birth to catch: Salmon hatch from eggs laid in freshwater streams, then travel through estuaries, where fresh meets salt water, and transition to the sea. There they thrive along the continental shelf for months–longer than we used to think, Welch has discovered. Some populations of certain species stay along the shelf near their natal homes; others stay along the shelf but migrate far distances up the coast; still others migrate up the coast and eventually out to the central Pacific.

Then, towards the end of their lives, they return to the fresh water streams—their natal ones, if they don’t get confused– to lay eggs. On return, they usually spend a few weeks in the coastal zone near their river of origin—and that’s where they’re usually caught for your plate.

So how clean are the waters your salmon has been living in? For that, we have to examine the rivers and lakes they come from, the estuaries, the coastlines and their migratory patterns along the coasts and into the open seas. Although salmon do get mixed up at times, each population generally follows the same pattern–meaning whether they originate in a river in Oregon or Alaska, most populations of a species take the same route to and from sea.

The general rule: Waters near industrial areas or large population centers are dirty. “The oceans have been used as toilets,” says Dr. Albert Tacon, a fish scientist for more than 35 years. That’s true of many rivers and lakes as well. Fish from the Great Lakes, for example, live in aquatic slums.

With this general rule in mind, let’s take a tour of the major swimming holes for wild Pacific salmon:

California, Oregon, Washington State (sold canned under the “Pacific” label): The Pacific coast has its fair share of major population centers. In fact, in 2006, Washington State’s Department of Health alerted consumers to avoid a certain species of salmon from Puget Sound, a major estuary of the Columbia River, because they were full of mercury and PCBs. Today, the alert is still in force while the government works on a clean-up plan. There’s no getting around the fact that the US Pacific coast is well-populated.

British Columbia (sold canned as “Pacific” or “Canadian”) : The southern tip, around Vancouver, is also full of people, and the fish suffer the consequences. As you move further north, however, the lack of industry and humans make the waters extremely clean. That makes salmon from northern BC more desirable than salmon that spend their lives in the polluted Strait of Georgia, a huge estuary between Vancouver Island and the BC mainland that adjoins Puget Sound to the south.

Now you might say: But how am I to know what part of BC my salmon comes from? You don’t. But keep reading, and we’ll solve the conundrum. Certain species stay primarily in that strait; others, including sockeye, spend a little time there and then migrate out to sea.

Alaska: And how clean are Alaska’s waters? Better than British Columbia’s? Do salmon really know geographical boundaries?

Many organizations that rate your fish (Monterey Bay Aquarium, Blue Ocean Institute, even Canada’s Seachoice) praise wild Alaskan as your premium choice.

And why is that? All the groups are measuring environmental impact—a laudable goal, but that’s not the question we’re asking. Alaska wins kudos for its sound management practices and secure stocks; sustainability is written into its state constitution, and its salmon survival in the wild is tops (although much of that could be due to its frigid waters, Welch suggests.)

But is Alaskan salmon really cleaner—that is, healthier for you– than BC salmon? That’s not the question these organizations are asking, and the answer all depends on where in Alaska your salmon comes from.

Dr. Michael Ikonomou, a DFO scientist, is one of the world’s foremost experts on contaminants in salmon.

Alaska’s Bering Sea v Everything South of it

“The Bering Sea is one of the most pristine bodies of water in the world,” says Ikonomou. So if your salmon is from the more northern parts of Alaska—caught in an estuary of the Bering Sea, yes, that would be the cleanest you could get, he says.

But have a look at a map of Alaska. It’s huge. And while the Bering Sea may be pristine, the waters around the Aleutian Islands in southern Alaska are a bit more contaminated.

“Compared to the Canadian Arctic, the Aleutian islands have been shown to be a little more vulnerable to contamination,” says Frank Stanek, DFO’s media relations manager. That’s due to local PCB contamination from old, decaying military sites along with industrial pollutants from far away. Because of their chemical and physical structures, those industrial pollutants migrate towards the cold Arctic, travelling northwards via air and sea from Asia. (Thanks, China.)

“To a large degree, there’s really no difference between salmon from southern Alaska and all of BC,” says Ikonomou, except for those species that reside in the Strait of Georgia. Southern Alaska and much of BC are very similar, with a few small population centers and pulp and paper factories creating some plumes of pollution along the coast. And some of the very best sockeye, according to an Alaskan fish distributor, are from two northern BC rivers–the Skeena and Nass.

Is your Alaskan salmon from somewhere else? Plus,have another look at that map of salmon migration patterns. As we discussed, all the migratory species, no matter where they originate along the Pacific coast, ultimately end up in the same offshore waters. No matter where your salmon starts out—from northern California to southern Alaska—each species of salmon follows the same distinct route.

Some specific populations (which you can’t see on the map) stay along the continental shelf their entire lives, either remaining near their natal waters or swimming long distances along the coast—all the way up to southeast Alaska—and then returning. They’re called coastal feeders. Others, called remote feeders, start out along the shelf and then swim up to the Aleutians and further out to open seas (as you can see on that map.)

Thus, all long-distance migrants, no matter where they originate, ultimately end up near Alaska’s coastline or in the offshore north Pacific before swimming back home and getting caught—or not—for human consumption.

“Fisheries in southern Alaska catch lots of BC salmon on their way back to natal waters,” says Welch, a frustrating situation for Canadian fishers. In fact, Alaska’s southern fisheries catch salmon that originate everywhere along the Pacific coast north of California. There’s simply no way of knowing where your Alaskan fish comes from if it’s caught along Alaska’s long southern coastline, unless you do a DNA test.

Alaska, it seems, has done a helluva snow job in its marketing.

Let’s examine some other factors that affect contaminant levels in salmon.

QUESTION 2: WHAT HAS YOUR SALMON BEEN EATING?

Chinook and Coho v Sockeye, Chum and Pink

The Chinook and coho species both feed on smaller fish for most of their lives and thus higher on the food chain than the other three species. That makes them more susceptible to industrial pollutants, which build up in the food supply. Sockeye, pink and chum, when they’re younger, feed lower on the food chain, on plankton, including small crustaceans and plants.

Plus, Chinook and coho are more likely to feed along the coastlines all their lives—and here geography does play a role. There are actually two kinds of Chinook and coho: those that feed along the coasts all their lives and those that travel out to sea and feed more remotely. Many populations of Chinook and coho are coastal feeders, making them more susceptible to toxins if they’re in a dirty area . In fact, many of BC’s Chinook and coho populations are coastal, meaning those species from the Strait of Georgia would be polluted. Chinook from Alaska, however, feed further out at sea, making Alaskan Chinook a safer choice.

Sockeye, pink and chum leave the coastlines and migrate out to sea, some further than others. Does that make them a better choice?

We’ve still got another factor to consider:

QUESTION 3: HOW OLD AND FAT IS THAT SPECIES YOU’RE EYEING?

“International studies show that the longer lived salmon species have higher levels of many contaminants compared to shorter lived species,” says Stanek. That’s another problem with Chinook and to a lesser degree, with coho and sockeye. As salmon go, they all live a fairly long time (especially Chinook) and accumulate fat, which makes them tasty. Chum also live a long while, but they’re the leanest of the species—in fact so lean that you have to eat a load of it to get enough omega 3s.

That brings us to pink salmon: They have more fat than chum, meaning more healthy omega 3s, as well as the shortest lifespan—around two years, meaning there’s much less time for pollutants to build up.

Ikonomou has studied in depth the contaminant levels in BC’s wild Pacific salmon, and here’s the order of cleanliness he found in his studies, from most PCBs to fewest:

Chinook–most PCBs

Sockeye and coho–medium

Pink and chum–cleanest

But the story doesn’t end here. Most of these fish could be acceptable choices, assuming you control your portions. In fact, as you’ll see if you stick with this series, some folks say that even farmed Atlantic salmon is acceptable these days from a health point of view. In order to get the recommended amount of omega 3s and the least amount of toxins, you have to regulate how much salmon you consume–and that amount will vary according to what species of salmon you’re selecting.

CONCLUSIONS So which Pacific salmon to choose? Is wild Alaskan really the best? It depends on where in Alaska your salmon comes from. Alaska’s Bering Sea is the cleanest ; beyond that, salmon from southern Alaska through British Columbia are pretty much the same, except for those that reside in BC’s polluted Strait of Georgia. If you like to eat a lot of salmon, choose pink–the cheap, canned variety. Or opt for other species, and just eat a bit less.

How much and how little? Which cans are best? We’ll get to the final answers by the end of this anti-cancer investigation. But first, let’s consider: Will Fukushima affect our wild Pacific salmon? Come back next week to find out.

© 2012 Harriet Sugar Miller For permission to reprint, contact hsugarmill@sympatico.ca.